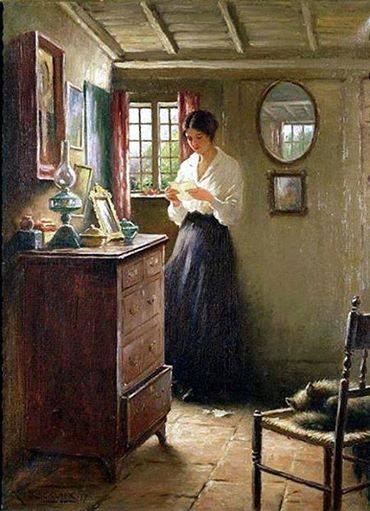

We are excited to have Andrew McEwan’s post about William Kay Blacklock’s painting The Letter highlight our new “Guest Posts Salon.” With the probing eye of a detective and the perceptive eye of an historian, Andy uncovers amazing clues in this beautiful painting. Noticing and appreciating details makes life richer. Enjoy!

William Kay Blacklock (1872-1922) was a painter very much of his time, the later Victorian and Edwardian periods, and, generally speaking, his oeuvre, in both content and style is very much like that of his many contemporaries who specialised in genre paintings in predominantly rural settings. It is probably fair to say that most of his pictures, again like those of many coevals, depict an idealised, even romanticised, view of rural life. While The Letter shares that rose-tinted setting, I think that the picture is worth a closer look because it touches on a darker element in a seemingly serene subject.

The setting of the picture is a room in a rural cottage. We can so conclude because the room has a roughly-flagged floor, a simple plank-boarded ceiling and is a small room: the window reflected in the mirror indicates that the room occupies the whole depth of the house. The bushes or trees seen through both windows reinforce the idea of a rural setting. There is no rug or carpet and furniture seen is sparse, comprising a simple rush-seat chair and a chest of drawers. This is not to say that the room is mean, as there are prints or pictures on the wall, as well as what seems likely to be a cased clock and the chest of drawers bears a handsome oil lamp, some simple bibelots and an ornate frame, possibly a photograph frame. A picture is painted, quite literally, of simple but decent domesticity, only added to by the cat depicted sleeping on the chair in the brightly sunlit room.

The painting shows a young woman reading a letter by the light of a window. She is pretty but her appearance is unaffected, dressed simply in a dark skirt and white blouse and her hair worn up in a simple style. At her feet, torn paper lies on the floor: we can surmise that she opened the letter in haste and let the envelope fall. This is uncharacteristically untidy considering the neat appearance both of the room and the young woman. Why such eagerness for news?

If we look closely at the paper the young woman holds, we can see that it has a dark border, no doubt the black border conventionally used to convey news of death or condolence. Who has died? We should note that the letter’s reader wears no rings: she is a single woman. Tellingly, the bottom drawer of the chest of drawers is slightly open, as if to suggest that the young woman had it open just before the letter arrived. The bottom drawer, of course, is where young women traditionally kept their troussseau in anticipation of subsequent marriage. I think we are inescapably led to the conclusion that the letter brings news of the death of the reader’s sweetheart or fiancé, whose photograph is most likely held in the ornate frame on the chest of drawers.

The Letter was painted in 1917, during the First World War and in a year which saw the Third Battle of Ypres, often referred to as Paschendaele, one of the bloodiest of the conflict and in which British forces incurred enormous casualties. Next of kin were notified of death by telegram but, of course, a fiancée would not be next of kin and would often learn of the death of their intended spouse in a letter from his parents or a comrade in arms.

And so, Blacklock’s seemingly simple depiction of a young woman reading a letter in an idyllic sunlit rural setting, in fact, depicts a far more sombre scene. The simple title, The Letter, could as easily have been, “Et in Arcadis ego”.

A.G. McEwan

Pamela’s Note: Et in Arcadia Ego is an intriguing Latin phrase with layered history and meaning. It is the title of Book One of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited in which a skull bearing the phrase acts as a metaphor for death and for a yearning for a lost paradise resulting from the transformation of war.

2 Comments

Carolyn Goodart

It was interesting to be drawn into this painting with more understanding of its meaning. After a second look at the painting I could see what the writer has mentioned. His comments were helpful, because we’re seeing this scene from another time and place.

TwointheMiddle

Just like you say, isn’t it interesting to notice details that you wouldn’t otherwise notice? I think it’s something like reading a good detective novel!